Tags

When we lived in Connecticut we had a ‘flock’ of hens. I use the term loosely; we had three hens. Ever since my grandmother told stories about making little rubbers for her chickens so their feet feet wouldn’t get wet, I wanted to raise chickens. It seemed more interactive than dolls, and less responsibility than actual children.

When we lived in Connecticut we had a ‘flock’ of hens. I use the term loosely; we had three hens. Ever since my grandmother told stories about making little rubbers for her chickens so their feet feet wouldn’t get wet, I wanted to raise chickens. It seemed more interactive than dolls, and less responsibility than actual children.

Our flock began with a gift of two small banty hens from a friend, which we augmented with the purchase of a Rhode Island Red and a Barred Plymouth Rock. Oh, they were lovely. One of the banties became despondent and went under the hen-house to die, but the other three lived with us until we gave them away upon leaving Connecticut, and they gave us just the right number of delicious small blue (the banty) and large brown (the other two) eggs.

In the U.S. the provenance of the eggs one buys is something of a mystery, as is their age. In a commercial operation, the eggs are washed and sanitized immediately, and then are sprayed with a thin coat of mineral oil ‘to preserve freshness,’ according to the USA Poultry & Egg Export Council. The quotation marks are mine, because I suspect it is done more to give the eggs a longer shelf life than for any other reason. When you buy a carton of eggs in the U.S., you have no idea where they’ve come from, unless the name of the farm is on the carton itself. And even then you have no way of knowing if the hens were caged or free-range, or what they were fed. (This is true: leftover bits of chicken at a processing plant are ground up and used as chicken feed. Blcch.) Fancier/organic egg producers are likely to advertise their practices on their cartons, but otherwise you’re left in the dark.

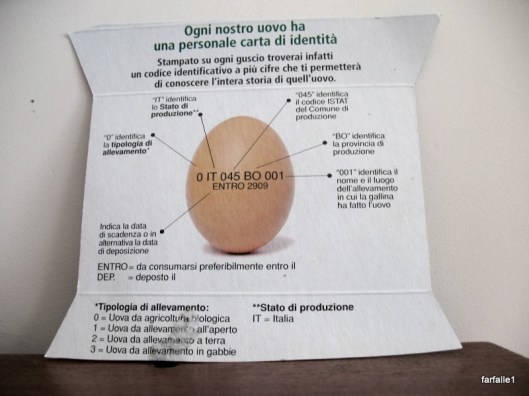

Here in Italy every commercially sold egg comes with a code stamped on it.

The first number identifies the life style of the producing hens: 0=biologic (what we might call ‘organic’ in the U.S.) 1 = living in the open (‘free range’) 2 = raised on the ground (something between free range and a cage) and 3 = caged. The next two letters give the country of origin of the eggs; the next three numbers correspond to the town where the egg was laid; the next two letters are the provincial code of the town; the last three numbers identify the name of the producer (not the hen, the farmer). So, no mystery about your egg here. Of course, not all eggs are equally legible.

This one is pretty clear (oh, busted! Now you know we buy eggs from unhappy cage-raised hens in the province of Bolzano. Shame on us.) Sometimes the printing is quite smudged so you have no idea what it says. Note also that there is a use-by date stamped under all the other info.

I haven’t been able to find out what Italian hens eat, but the yolks of their eggs are a rich red-yellow, almost orange. When we go back to the  States the relatively pale yellow yolks seem anemic to us. But I must say, even our own flock of Connecticut hens produced the pale American yolk. It must be something in the Italian diet … even for the chickens.

States the relatively pale yellow yolks seem anemic to us. But I must say, even our own flock of Connecticut hens produced the pale American yolk. It must be something in the Italian diet … even for the chickens.

We always feel good about buying eggs here. The laying date is stamped on the egg box (they’re sold in quantities of 4, 6 or 10, an odd mix of metric and imperial measurement). The egg itself will tell us exactly where it comes from. Italian eggs are not sold from refrigerated cases. They sit out on the shelf, proud to be fresh enough to do so.

Good as the eggs in the market are, though, the best egg is the one with no identifying marks, save perhaps a little bit of hay or something worse stuck to it, the egg your neighbor gives you.

I have to laugh – when my Italian-born husband speaks of eggs – and as most Italians I know speak of the yolks, they refer to the ‘red’ of the egg and not the yellow!

Bonnie(valentinoswife)

True, but you can see why – the yolk here is almost red colored. I guess we’d have to call it ‘straw’ or ‘yellow’ if we didn’t call it yolk. Here the white is called albume – not bianco. Go figure.

Oh now you’ve done it! I so wish that we could raise hens (’tis true…the less responsibility part) but it simply wouldn’t work with the space restraints and the neighbors. I absolutely loved the part about your grandma telling of making rubbers for her brood.

I remember doing an egg show-n-tell years ago on another ‘web journal’ and all I can say is that the folks stateside had no clue what to say? All that bit of info was a little too much, I’d like to think. Perhaps that was the general mentality back then? I know that MotH was always dubious about eating eggs after the stamped date.

ps. where did you find a jar lifter? I’ve been hunting for one of those.

We carried one back from the States this year. My neice is coming over shortly – shall I ask her to bring one for you? It takes no space at all in the luggage… in fact, I just wrote and asked her to do so, if it’s not a hassle…

When you return to the states, I must get you to “The Egg Lady”. We have been buying her eggs for some time now and could not be happier. They have those deep orange-yellow yolks, nice dirty shells but best of all, they taste richly egg-y. We scrambled some this morning and realized they have spoiled us for the store-boughten kind.

BTW – on American grocery store egg cartons, there is a lot of meaningless verbiage about “free-range” hens which is absolutely meaningless. Ditto for “cage-free”, “grass-fed” or a lot of other happy-chicken sounding terms.

The expiration date is also pretty meaningless since eggs will last for weeks, not just days. Check the two or three digit number after the expiration date (59 or 144, etc) and that tells you what day of the year the eggs were packed. This is no guarantee of the eggs being laid on that date, simply that they were packed on (59) February 28th or (144) May 24th.

When in doubt about the freshness of a raw egg, place it in water. If it floats you should – gently – discard it as it is rotten. Eggs remaining under water are still fresh. I learned this keen kitchen truc on a sailboat and have never looked back, not have I ever gotten an old, floating egg.

Yes, yes, pray take me to your egg lady! I’ll have to study the American cartons more carefully the next time I’m in the same room with one. We left an egg in the running fridge in Arizona after the first winter we were there. When we came back the next winter it was completely light and felt hollow – all the water inside had evaporated. We still have it; half of me wants to keep it as a curiousity, the other half wants to open it up to see what gnarled little thing is inside…

I have long longed for some more “Helen” eggs – and lo and behold! the co-op I buy from now has farm eggs – the real kind with a bit of this and that stuck to them. They have deep, orange-red yolks…so I shall ask what they’re fed and pass that bit of trivia on to you…carrots? red chard? sweet potatoes? beets? earth worms? Whatever it is they are delicious – and fresh!

Our hens pecked around the yard a lot, but most of their nourishment did come from commercial feed; that’s probably why they laid pale eggs. Once I saw one eat a whole big toad – that was pretty gross, but interesting. Glad you’ve got really good fresh eggs now.